The following biography

has been adapted from my 2009 book and updated to include information from

Charles’s military service record, oral histories of men who served alongside

him and a Far East Prisoners of War questionnaire that he completed on his

return from captivity:

Charles Alfred Hand, or

grandpop as he was known to me, was born on 21st August 1918 at 14

Mary’s Terrace, Twickenham, Middlesex. He probably didn’t remember very much

about his early years in Twickenham, but the house backed on to the railway

station and he would have heard the steam trains going past on their way to

London.

|

| Family tree |

At a young age he moved

to Edinburgh with his parents and his older siblings William and Doris. Little

is known about this period of his life, but we know he spent his school years

in Scotland and he received a good education. During this time his older sister

Doris met and married a soldier named George Highley. At the time of the

wedding, the family were living at 9 Northfield Road situated to the east of

the city centre. After the wedding his sister and her new husband moved to

India. Meanwhile, his brother William moved back to England in the 1930s and

became a structural engineer. By the end of the decade, Charles had moved back

to England with his parents and according to the 1939 electoral roll they were

living at 85 Lyndhurst Avenue, Whitton. Soon afterwards he started working for

the civil service.

In April 1939, with the

threat of war growing, the government introduced the Military Training Act. The

terms of the act meant that all men aged between 20 and 21 had to register for

6 months military training. Charles would have been affected by this

legislation. By September 1939, Britain was once again at war and on 19th

October Charles received his conscription papers.

Army Training

Charles enlisted with the

162 Field Ambulance of the Royal Army Medical Corps on 19th October

1939, but according to his military record, was posted to the 197 Field

Ambulance on 11th January 1940. Charles and the rest of his unit

boarded a train up to Norfolk and arrived at the village of Hillington near

Kings Lynn. From here they marched through thick snow to a nearby hall. By May

1940, the unit was put to good use as Germany had invaded France and the Low

Countries and the first Luftwaffe raids were seen. At this time, the 197FA was

based at Cranwich Camp in Norfolk and in addition to dealing with the wounded

from air raids, Charles would have been sent on various training courses. By

the end of 1940, they had moved to nearby Lynford Hall which functioned as a

training hospital. It was during his time here that Charles was disciplined for

serving breakfast to patients on cold plates and on a separate occasion, for

not washing up dirty plates. Both times he was fined 2 days’ wages.

As a part of their

training, the 197 FA travelled to various locations in England and Scotland

during 1941. The unit was then given disembarkation leave at a rate of 30% of

the unit a week starting 26th September 1941. This leave lasted for

7 days. At the end of his leave, on 8th October 1941, he was posted

to the 196 Field Ambulance and reported to a tented camp at Norton Manor near

Presteigne on the Anglo Welsh borders. Here he continued training as a part of

the 54th Brigade, 18th (East Anglia) Division.

At 0830 hours on 27th

October 1941 they marched through the streets of Presteigne to a special troop

train that took them to Avonmouth on the Bristol Channel.

Off to war

The men boarded the SS

Oransay, which was an Orient Line British ship of 20000 tonnes. On 28th

October 1941 the SS Oransay left Avonmouth and headed up the English coast in

stormy weather, with nearly all of the 196 and 3000 other troops. On 30th

October the SS Oransay arrived in Greenock, Scotland were it joined the rest of

the fleet for an, unknown at the time, journey across the Atlantic to Halifax,

Nova Scotia in Canada.

On 2nd

November, in the middle of the Atlantic, the British convoy met up with an

escort of US Navy ships who would provide protection during the remainder of

the crossing. They arrived in Halifax on 7th November and Charles

would barely have had time to stretch his legs before embarking once again to

some unknown destination. The 196 and most of the accompanying division were

kitted out for desert fighting, so speculation ran that they were set for

Africa or the Middle East. Transport this time was provided by the US Navy and

Charles departed with the rest of the 196 on the USS Joseph T Dickman, an

American troop ship. The convoy set sail on 10th November 1941 and

had arrived on 22nd November in Trinidad in the West Indies to

refuel. There was no time to disembark and the convoy set sail once again.

By early December the

unit arrived in Cape Town, South Africa and was given four/five days shore

leave. This must have been a welcome relief to Charles and the rest of the unit

having spent 10 weeks at sea.

The 196 spent Christmas

Day 1941 aboard the Joseph T Dickman. The menu was roast turkey, giblet gravy,

pickles, sage dressing, cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes and buttered peas

followed by plum pudding, camper down sauce and fruit salad. There was also

bread, candy, tea, cookies, butter and cigarettes. The ships food was

apparently complemented by many in the unit.

The 27th

December saw the unit arrive in Bombay, India, where they disembarked before

getting on a train to Ahmednagar, where they stayed for around two weeks. The

next stage of Charles’s epic journey was a train journey back to Bombay

followed by another sea journey on board the USS West Point which left port on

19th January 1942. This leg of the journey saw the first encounters

with the Japanese, as an escort vessel fired on a Japanese plane, apparently on

a reconnaissance mission. The Japanese had invaded the Malay peninsula on 7th

December 1941 and were moving south in the direction of Singapore.

The USS West Point

arrived at Keppel Harbour, Singapore on 29th January 1942. Charles

and the 196 disembarked and were taken by lorries to a tented camp on the

Tampines Road. They were to provide medical treatment to the soldiers of the 54th

Brigade who were now deployed in the north-east sector of the island and set up

a series of remote dressing stations. The men of the Royal Army Medical Corps

were not issued with any weapons and relied on the fighting troops around them

for protection. This part of the island faced Malaya across the Johore Straits,

where the Japanese had been steadily advancing and were expected to attack

from.

On 1st

February 1942, the unit experienced the first enemy activity with artillery

fire and aerial bombing. Between 2nd and 5th February the

unit maintained its position and treated the wounded from the Japanese attacks.

The minor sick were treated and held in the dressing stations, with the major

casualties evacuated in ambulances, to one of three hospitals in Singapore

City.

The Japanese landed on

Singapore island late on 8th February in the north-western sector,

which was held by 8th Australian Division. They quickly established

a bridgehead and began to work their way towards Singapore City. By 13th

February the 196 were deployed in the Thompson Road/Bukit Timah Road area of

the island just north of Singapore City. The unit was shelled and were almost

immediately ordered to move from that location. The unit came under Japanese

rifle fire as it prepared to move. The further withdrawal resulted in the main

dressing station (MDS) being set up in the City High School at around 1800

hours.

The 14th

February was the busiest day for the unit and they treated large numbers of

casualties. The situation was now very difficult and dangerous with men evacuating

the wounded from the front line back to the MDS in the face of enemy fire. The

morning of Sunday 15th February saw large numbers of severe

casualties received at the MDS with a report of over 200 wounded being treated.

By now the City High School building itself was coming under attack from mortar

shells and it must have been terrifying. By 4pm the shelling stopped and a

final “all clear” siren sounded. By now the Japanese had complete air

superiority and had captured the island’s water reservoirs, leaving the

commander of the Allied forces in Singapore no choice but to unconditionally

surrender the city and the island to the Japanese.

|

| Japanese FEPOW card |

Captivity

Charles and the rest of

the unit remained at the City High School until 22nd February when

they were ordered to march to Roberts Barracks in Changi, on the east side of

the island, around 15 miles from the school. Here the unit continued to treat

the sick under very cramped conditions. There were no functioning lavatories

and the medical supplies were limited.

As time went on,

conditions and the treatment of the men started to deteriorate. The diet was

the main issue with very little food given out and there were very few Red

Cross parcels reaching the men, as the Japanese held them back. With virtually

the only food available being boiled rice, the men started to contract diseases

such as Dysentery and Beri Beri, due to lack of vitamins.

From June 1942, the men

were told that they would be sent away to “holiday camps”. Charles’ turn came

on 5th November 1942. He was transported with “Party M” firstly by

truck to Singapore Railway station and then north by train in steel cattle

wagons. The men were transported 35 to a wagon and by day these wagons became

very hot and at night very cold. The doors did not shut properly and the rain

would drive in. To sleep in these cramped conditions was near impossible.

The journey up the length

of Malaya passed Kuala Lumpur and Prei Station near the beautiful island of

Penang. Food was provided in a bucket, one bucket of boiled rice per truck per

day, in the heat the rice went off and it wasn’t long before the men’s health suffered.

Most of the prisoners suffered from Dysentery and there was only one bucket per

truck. Occasionally the Japanese would stop by the train and the men would

relieve themselves by the side of the tracks.

Five days after leaving

Singapore, the train arrived in Ban Pong, Thailand at the start of what was to

be the infamous Burma Railway. Here, they were greeted by more Japanese guards

shouting “marchy marchy” and the men were marched to a nearby camp. The camp

leader at Ban Pong was Lt Col Malcolm. Charles remained here until Christmas

Eve. From here Charles was marched to a camp at the nearby village of Nong

Pladuk which was at the southern end of the Burma railway.

Dysentery and flies were

rife and the hospital lay at the lowest part of the camp and was often flooded.

The hospital was an Atap hut (constructed with a bamboo roof and open sides)

and at times the patients were laying only inches above the flood water on

their bamboo shelving. It was not uncommon for the doctor to visit the patients

in Wellington boots and then climb onto the shelving as the water was too deep

to stand in. Mosquitoes took over the area at night and brought more illness to

the already sick patients.

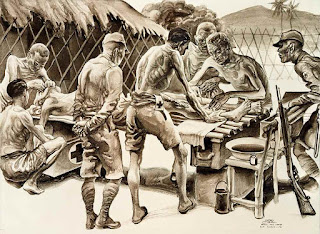

|

| Conditions inside an Atap hut |

Charles was moved up

country on 25th March 1943 to work on the railway. At the railway

camps, there were frequent beatings and sick men were dragged from their beds

to work. The medical officers and orderlies working in the camp hospitals would

do their best to prevent the seriously ill patients from working and this would

often result in a beating from the Japanese guards. The sadism and cruelty of

the Japanese guards knew no bounds but it was the Kempetai, the Japanese

Gestapo, who were feared the most for their methods of torture. Charles would

have dealt with the consequences of this on an almost daily basis and is highly

likely to have been on the receiving end of Japanese brutality himself.

Apart from Cholera,

diseases like Diarrhoea, Dysentery, Beri Beri and Malaria were universal and

kept the medical staff busy. The Japanese had been withholding food and medical

supplies but the monsoon made it impossible to transport these goods in any

case. Charles and the other medical staff had to do their best to comfort dying

men with no drugs. They felt so helpless that they could do little for these

poor people, yet their ingenuity still saved many lives. Bed pans were made

from large bamboos and cannulas for intravenous saline injections from bamboo

tips. There were limb amputations to save patients dying from gangrenous

tropical ulcers and artificial limbs made from timber. The biggest factor for

saving lives was the courage and compassion of the medical staff that had to

work in the most extreme circumstances. There were some dreadful sights on the

wards - men who were only parchment and bone. These scenes would have scarred

Charles for life.

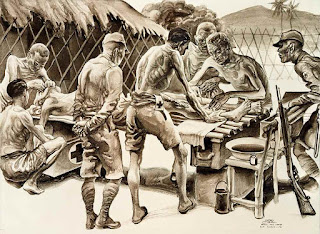

|

| Treating a patient with tropical ulcers |

Hospitalised men were

only entitled to 250-300g rice per day with a small quantity of beans. To the

Japanese, men who held up the construction of the railway due to lack of health

were guilty of a shameful deed. Despite widespread disease, men continued to be

dragged from their beds to do heavy physical work.

The records do not name

the camps where he was imprisoned but at the time his commanding officer was Lt

Col Flowers of the 9th battalion of the Royal Northumberland

Fusiliers. From his CO’s record it can be assumed that Charles was at Hindato

camp, some 200km from Nong Pladuk, on Christmas Day 1943. By this time, construction work on the railway

had been completed and most of the medical staff were subsequently sent back

down the line in cattle trucks to work in the camp hospitals at Chungkai and

Nong Pladuk. Charles arrived at Nong Pladuk II Hospital in February 1944. Conditions,

though still severe, were not as bad as they had been further north. Charles was

moved to the newly created Nakom Patom camp in March 1944 where he spent the

remainder of the war. His commanding officer was Lt Col. Coates of the

Australian Imperial Forces. Here, he treated

patients with nothing but the most basic equipment and under constant threat of

beatings from the Japanese guards.

Following the dropping of

the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese surrendered on 15th

August 1945. With tens of thousands of Allied POWs all over South-East Asia,

the task of getting them all home was huge. Firstly leaflets were dropped from

aircraft telling them to stay where they were. Shortly afterwards items from

clothing and boots to food and medical supplies were dropped. Charles was

liberated by allied forces on 21st September 1945 and was finally

transported by train to Bangkok before being put on a plane for a short flight

to Rangoon in Burma.

The men who arrived in

Rangoon were treated with kindness. They were taken to a room set with tables

with white cloths and flower arrangements. They were served white sandwiches of

butter and cheese. English girls waited on them. The first white women the men

had seen in years.

In late September 1945

Charles would have boarded a ship that sailed to England via Colombo and Port

Said. The voyage would have taken about a month and his ship docked at

Southampton on 28th October. Once on British soil, he was taken to a

military disembarkation camp before finally being allowed home to be reunited

with his family.

Life after war

The Far East POWs

(FEPOWs) had one short interview and completed a brief questionaire before they were demobbed and returned to

their civilian lives. After a period of leave, Charles returned to work as a

civil servant at the newly-formed Ministry for National Insurance even though

he was still emaciated from his time in Thailand. It would take him years to

put the weight back on.

Charles’s obvious joy at being back home was

tempered by the news that his older brother, Bill, had died during his period

in captivity. His widow, Connie had been left to bring up her daughter Maureen

by herself during the war years. Charles’s father had helped her through this

difficult period but wanted to do more.

The decision was taken

that Connie and Charles should get married. It was a practical solution and it

isn’t clear whether Charles and Connie actually loved each other at that time,

although they certainly did as they grew to know each other over the years.

They were married on 29th March 1947 at Saint Peter and Paul RC

Church in Ilford.

Charles and Connie’s

first child, Theresa, my mother, was born on 14th July 1948 in

Selsdon, Surrey. Soon after Theresa’s birth, Charles was transferred and the

family moved to Nottingham. They lived at 10 Catterley Hill Road until around

Christmas 1952. Whilst they were living in Nottingham, Charles’s father passed

away and in February 1951 he had to return south briefly to register his death.

The responsibility fell to him as his sister lived far away.

On returning south, Charles

and his young family moved to 57 Parkside Avenue, Romford, Essex. Connie was

pregnant and Janet was born on 15th March 1953.

Charles’s wartime

experiences continued to haunt him. He had recurring bouts of Malaria but it

was the mental scars that were worse. He struggled to cope with the daily

challenges of life and suffered from periods of depression and these were

perhaps exacerbated by feelings of grief surrounding his father‘s death. Today

these symptoms would be recognised as post-traumatic stress disorder, but they

were not so well-understood in the 1950s. My mum has memories of him being

taken away in an ambulance for electric shock therapy. He would return home,

wrapped in a towel, and would be placed in a chair. He would pick up a

newspaper which he would hold upside down in front of his face.

Charles was eventually

prescribed with lithium tablets which brought his symptoms under control. The

tablets helped him to regain control of his life but they were to have serious

repercussions for his health later in life.

|

| Left to right: Janet, Charles and Connie |

Life improved and Charles

and Connie gave birth to another daughter, Clare Elizabeth Hand, on 23rd

January 1961. By this time Theresa and Janet were at school. Theresa was

attending the Ursuline convent school in Brentwood and Janet would have

attended a local primary school. Maureen married Brian White in 1964 and in

1966 she gave birth to a son of her own named Darren.

Circa 1967, Charles and

his family moved from Romford to a large house in The Warren, Billericay. The house had a large garden and a double

garage. Everybody loved the house. At the time of the move, Theresa had left

school and was working in London. Janet had moved up to the Ursuline and Clare

was old enough to go to primary school.

At around the time of the

move, Charles had lost his job at the civil service. They had grown weary of

his absenteeism due to his poor mental health and had forced him out. Charles

managed to secure work with the post office and then later with the insurance

firm Eagle Star. All this helped to pay the bills but he was not earning as

much as when he was with the civil service and he had also lost out on the

lucrative civil service pension.

Theresa was married to

Keith Melton on 18th October 1969. The service took place at the

Most Holy Redeemer RC church in Billericay and was a very happy occasion. Less

than four years later, Janet married Brian Jewell at the same church. Clare,

who was by now old enough to attend the Mayflower school in Billericay, was a

bridesmaid at both weddings.

As the carefree and

prosperous 1960s gave way to the 1970s the economic dark clouds began to

gather. Bills rose and they could no longer afford to make ends meet. In 1974

Charles, Connie and Clare, were forced to move to a smaller house at 167

Mountnessing Road, Billericay. Charles and Connie had hoped to have some money

for their retirement but the rates were just as high in the new house. Charles

retired from work in 1978 and still faced financial uncertainty.

The wedding of Clare to

Martin Gale on 4th June 1983 meant that Charles and Connie were

alone for the first time in their marriage. The wedding, once again, took place

at the Most Holy Redeemer RC church and this was followed by a reception at a

hotel in Basildon.

With all of the daughters

now married, Charles and Connie were free to spend their retirement years in

any way they wished. In 1984 they moved from Billericay to a newly-built

bungalow at 4 Grimston Way in Walton-on-the-Naze. These were happy times and

they made friends with other couples who had retired to the Essex coast. They

had a good social life and fresh air was good for their health.

We would regularly visit

them at weekends for Saturday or Sunday tea. During the summer holidays, my sister

and I would spend a week with them. They would sometimes rent a beach hut for

the duration of our stay and we would have many happy days by the beach playing

in the sea when it was sunny or playing cards inside the hut over a cup of tea

if it rained.

|

| Charles and Connie with a friend |

Charles never forgot his

wartime experiences and would attend annual Remembrance Sunday parades in

London with other FEPOWs. Sometimes, over tea and cake on a Saturday afternoon,

he would talk to me and Dad about his wartime experiences. He would talk about

his hatred of the Japanese and his helplessness at being unable to treat the

sick due to lack of supplies.

In 1997 Charles and

Connie celebrated their golden wedding anniversary. The family took them out

for a meal at a local restaurant called “Harbour Lights” and it was quite an

occasion.

By this time Charles’ was

suffering from kidney disease which had been caused by his long-term use of

lithium. Following his diagnosis, he spent several weeks in hospital at Black

Notley. His condition stabilised with the use of new medication, but now he had

to get used to having regular dialysis which he could have at home, although he

still needed to attend out-patients’ appointments.

In spite of receiving

treatment his condition gradually worsened and he was admitted to Ipswich

hospital. He sadly died there on 20th February 1998 aged 79.

Further reading: