|

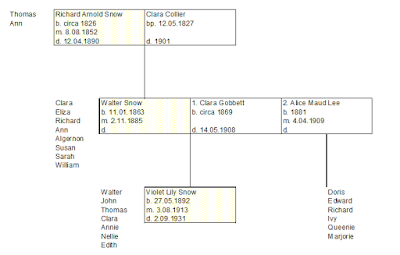

| Snow family tree |

Richard Arnold Snow was born in Braintree, Essex and baptised at St Michael the Archangel church on 15th June 1826. He was the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Snow and Thomas, who was originally from the village of Great Waltham, was a pig dealer. His mother Elizabeth, who had been born Elizabeth Arnold, was originally from nearby Kelvedon. The couple had been married for 2 years at this point and already had a daughter, Eliza.

|

| Baptism record |

As a pig dealer, Richard's father would buy livestock either from local agricultural fairs or directly from farmers. In the 1840s and prior to the development of the railways, these animals were transported across the country on foot. They would be fitted with iron shoes rather like horseshoes and walked long distances accompanied by the salesmen and their assistants, the drovers. Depending on the season, the pigs would be sold on at markets to be slaughtered or lead to pasturelands to be fattened up. The job involved staying away from home and travelling great distances.

In August 1844, when Richard was just 18 years old, his father passed away. The funeral took place on 15th August at the church of St Michael the Archangel in Braintree. This event, as sad as it was, would have been one of the most important events of his life. We don't know what happened in the immediate aftermath of his fathers death, but four years later the Post Office Directory shows that he had moved to London and was running a ham and beef shop at 34 High Holborn. His business is also listed in the 1850 P.O. Directory, However, by the time of the census the following year the 25 year old Richard was lodging at 21 Ormsby Street in Shoreditch and was reduced to sharing a room with a 21 year old wood block carver in a house run by a widow named Elizabeth Baines. She lived on the premises with her sister and nephew with Richard and the wood carver occupying one of the rooms with the remaining room containing two further lodgers. His business the business had evidently failed as he was now working as a cattle salesman, similar to his father.

|

| Ormsby Street 1976 |

After the wedding, Richard and Clara remained in Shoreditch, possibly with her family, but it wasn’t long before they started a family of their own. Their first daughter, Clara, was born in the spring of the following year. She was followed by Eliza who was born in the early months of 1855. Unfortunately, by this time Richard's past business debts had caught up with him and he was forced to apply for an interim order at the court for the relief of insolvent debtors in a bid to try and prevent legal proceedings against him. The order required him to attend a hearing at the court house in Portugal Street, Lincolns Inn so that any mitigating circumstances could be assessed. Richard attended the court on Thursday 1st March 1855 at 11am and whatever he said on that morning must have kept him out of debtors prison as there is no record that he was ever incarcerated.

|

| Extract from the London Gazette |

The article above describes Richard as a salesman's assistant and a licensed drover. In those days the hours during which cattle could be moved through the streets were strictly regulated. No cattle were permitted to be driven to Smithfield Fair before midnight on a Sunday, while it was forbidden to drive animals within one mile of Smithfield before 11 pm on market days. Anyone breaching these rules could be prosecuted. It was possible, however, after 1867, to drive cattle through the streets of London, provided the prior permission of the police commissioner had been obtained. Such regulations applied both to local city drovers and to those persons bringing cattle from afar. Public concern with the barbaric ways with which the city drovers frequently treated their cattle prompted the Mayor's Court to issue an ordinance forbidding drovers from using '. . . any stick or other instrument the point of which shall be of greater length than one quarter of an inch ‘. Any drovers caught using sticks which had not been approved by the Clerk of the Court and marked accordingly, could be fined a sum up to forty shillings.

|

| Birds eye view of Smithfield Market |

In Oliver Twist, which Charles Dickens wrote in the late 1830s, he described Smithfield as being covered "nearly ankle deep with filth and mire: a thick steam perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle" with it's "unwashed, unshaven, squalid and dirty figures", the market was "a stunning bewildering scene which quite confounded the senses" Dickens' account gives us a good idea of what Smithfield must have been like when it was a 'live' meat market, when cattle were driven to market to be slaughtered on site. It was not until 1855 that the 'live' meat market was moved further north to Copenhagen Fields in Islington.

Richard's first son, Richard, was born in early 1857, they had moved to a place of their own in Hackney. Records suggest they remained in Hackney for about three and a half years before moving slightly further east to Homerton, which at the time still had a rural atmosphere. They moved into Geranium Cottage at no.3 Sydney Road at the junction with Marsh Hill. Marsh Hill, as the name implies, was the eastern extension of the High Street that lead downhill out of Homerton towards Hackney Marshes. The marshes were used at certain times of year under Lammas rights as grazing lands and this was probably an important factor in Richard’s decision to move to the area. Homerton also had decent amenities. At the time shops, lined both sides of the High Street and there were seven public houses.

|

| Homerton High Street c1870 |

Not long after moving there and at some time during the final months of 1860, Clara gave birth to twins whom they named Algernon Robert and Susan Catherine. Richard seems to have been making a success of his life as a cattle dealer because not only had he managed to move his family out to the relatively leafy suburbs, but he could also afford to employ a young servant girl. Richard and Clara’s third son, Walter, was born on 11th January 1863. His birth was followed by more children: Sarah Jane in spring 1865 and William James in the summer months of 1868.

The 1860s were not all plain sailing for Richard. In 1867 there was a nationwide outbreak of cattle plague which would have lead to restrictions in the movement of cattle. The Times newspaper for 12th September 1867 contains an article reporting a fresh case of the disease on Hackney Marshes. The unfortunate animal died along with 278,927 others across the country during the course of the outbreak. In addition to these deaths, the government’s veterinary office culled a further 56,911 healthy cattle in a bid to prevent the spread of the disease. This must have damaged Richard’s business and this may have been a period of hardship for him and his family. The other significant event of the decade was the opening of Homerton railway station in 1868. This was to be the catalyst for much speculative land development and spelled the end of rural Homerton. In spite of these challenges, Richard and his family remained at Geranium Cottage and he even had time to indulge in one of his favourite hobbies: fishing. The Chelmsford Chronicle dated Friday 13th November carried the following article:

By the time of the 1871 census, Richard was working as a cattle drover and as such, probably spent periods away from home. His daughters Clara and Eliza had grown up and were working as teachers and his younger children were attending school.

|

| 1871 census |

|

| 1881 census |

In the years that followed, Richard’s livelihood eventually recovered and he resumed work as a cattle salesman. This turn around in fortune made it possible for him to leave the increasingly dirty and industrialised surroundings of Temple Mills to a more salubrious neighbourhood. They moved to 114 Olinda Road in Stamford Hill. At the time Stamford Hill was already growing in population due to the migration of the more successful people from the East End and it already had a small but growing Jewish community. Unfortunately for Richard, just as his economic situation was improving, he started suffering from ill health and he was diagnosed with heart disease. Richard died a year after his diagnosis, on the 12th April 1890, with his daughter Anne by his side. He was 64 years old. The family laid him to rest in West Ham Cemetery alongside his son, Algernon.